Twice - 1980s

The 1980s saw the second major push to name the stadium after Trice. Despite the Board of Regents’ vote to delay naming the football stadium in 1976, students continued to show their support for Jack Trice Stadium through passing resolutions and bills in the Government of the Student Body and by demonstrating their support in highly visible ways. It was assumed that the University would own the stadium by the Spring of 1984, giving the students a new deadline.

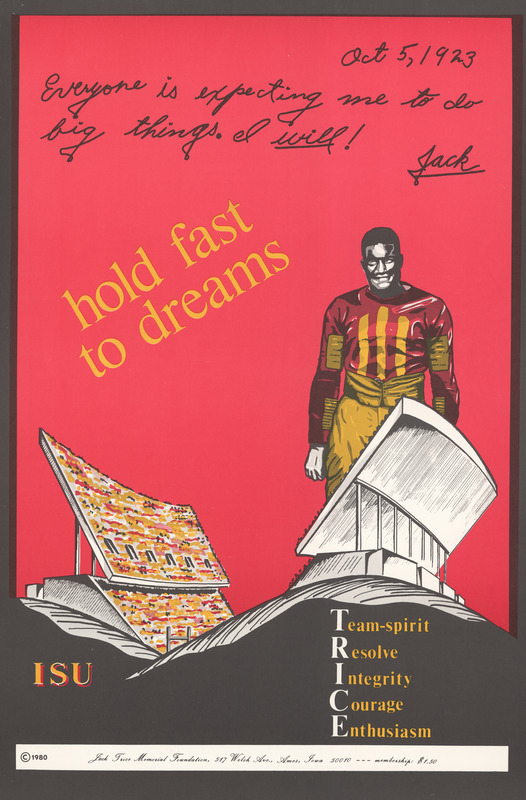

During the VEISHEA 1980 celebration, the Jack Trice Memorial Foundation had a booth as part of the open house displays. They shared displays and distributed information at the booth, including a ticket to obtain this poster and the mailer, seen below, about Trice and his ideals.

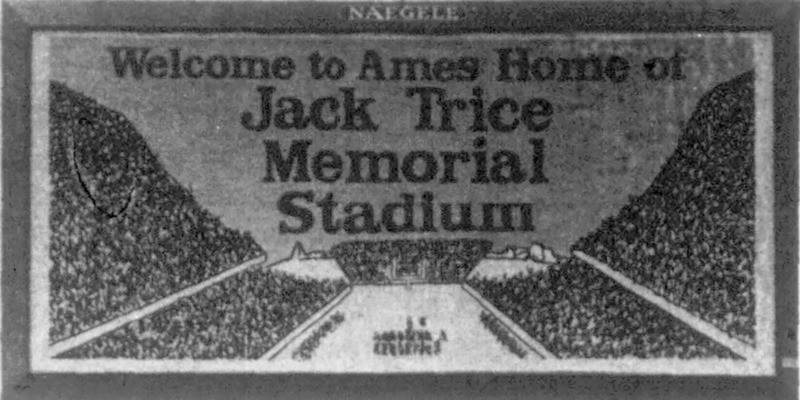

In the fall of 1980, students started a marketing push to expand their efforts to gain support for naming the stadium in Trice’s honor. During the October 25, 1980, game against Oklahoma, an airplane circled over the stadium for 40 minutes, trailed by a banner that read “Welcome to Jack Trice Stadium.” The banner was the idea of Greg Douglas, GSB President, and Tom Jackson, GSB Vice President, who independently funded the plane.

Over the summer of 1981, ISU students Steve deProsse and Rick Yoder developed a plan for a billboard to keep alive the idea of naming the stadium in honor of Trice. The billboard idea was inspired by the airplane from the previous fall with the hope that it would have a larger impact since it would be up for a month.

The billboard was installed in late August near the corner of Lincoln Way and Sherman Avenue at the cost of $240, which had been provided by the Iowa Public Interest Research Group (IPIRG). Private donations were solicited to repay IPIRG.

Following a debate by GSB Senators, a vote was held to allocate funds to promote the stadium’s naming in honor of Trice during the game against Nebraska on November 15, 1980. Money was set aside for flyers, radio spots, an airplane, a banner, and a newspaper ad. During the game, radio spots ran on three radio stations in Ames and one in Shenandoah. A station in Des Moines refused to run the ad based on the Fairness Doctrine.

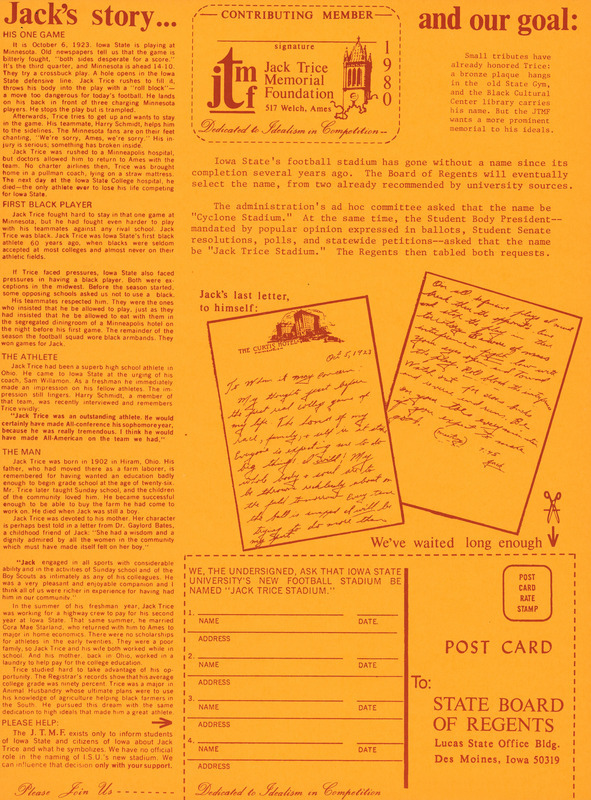

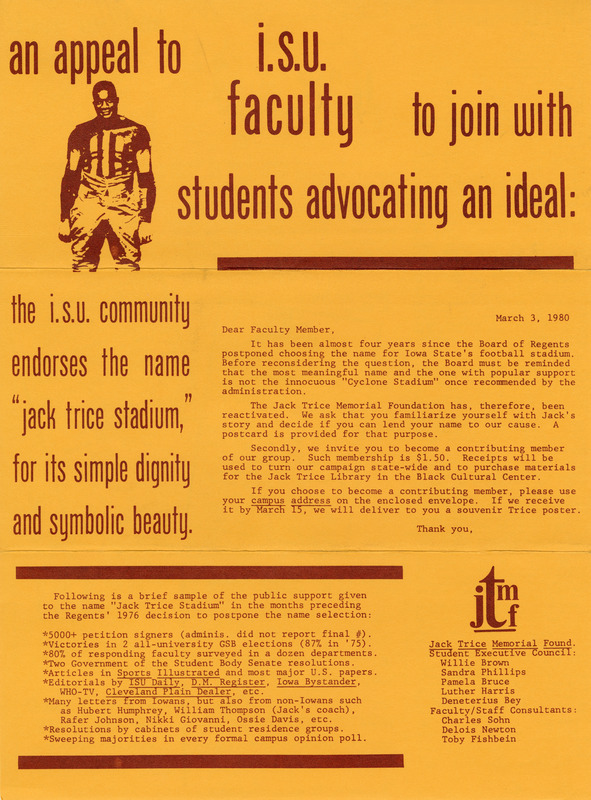

Support for naming the football stadium in honor of Jack Trice was consistently strong among the student body, as evidenced by student-signed petitions, GSB legislation, and resolutions by student organizations. The Jack Trice Memorial Foundation worked to garner support from the ISU Faculty as well by polling faculty on their stance and by soliciting their support by inviting them to join the Foundation and to send postcards supporting the naming of the stadium after Trice to the Board of Regents.

The Government of the Student Body continued their support of naming the football stadium in honor of Jack Trice through the early 1980s. The GSB Senate passed Resolution #83-001R supporting the naming of the stadium for Trice and designated the October 8 game versus Kansas, the 60th anniversary of Trice’s death, to be dedicated in his honor. Days before the game, Athletic Department officials decided not to support the idea but later agreed to have a moment of silence during the 3rd quarter.

At a tailgate party before the game, signatures were gathered to support naming the stadium for Trice, and black armbands were passed out to those in attendance. An estimated 300-400 fans wore the armbands along with members of the band and Cy. The armbands harkened back to 1923 when Trice’s teammates wore black armbands for the rest of the season after his death.

Another tailgate was organized for the last game of the season, as it was anticipated that the University would take ownership of the stadium sometime in the spring, and the Regents would finally move to name it. At the game against Oklahoma State on November 19, fans again sported black armbands, while members of the band wore either black or white armbands to show their support in honor of Trice.

After the University took possession of the new stadium, President Parks moved to have the stadium named during the December 15, 1983, Board of Regents meeting. Parks recommended the stadium be named “Cyclone Stadium” and the playing surface “Jack Trice Field.” Student, faculty, and staff representatives at the meeting asked that a vote be delayed until the spring Board meeting in Ames. After a failed motion to name the stadium “Jack Trice-Cyclone Stadium,” a motion was made for a vote on President Parks’ recommendation. This vote passed unanimously.

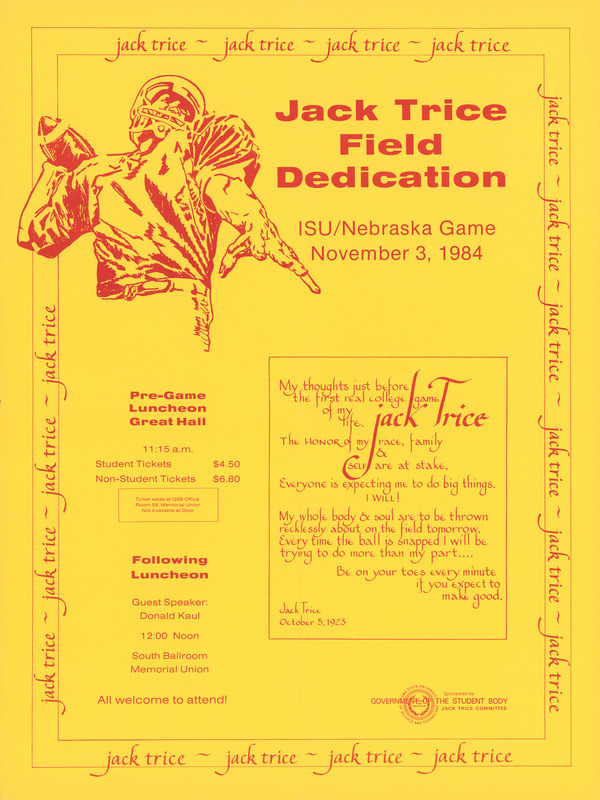

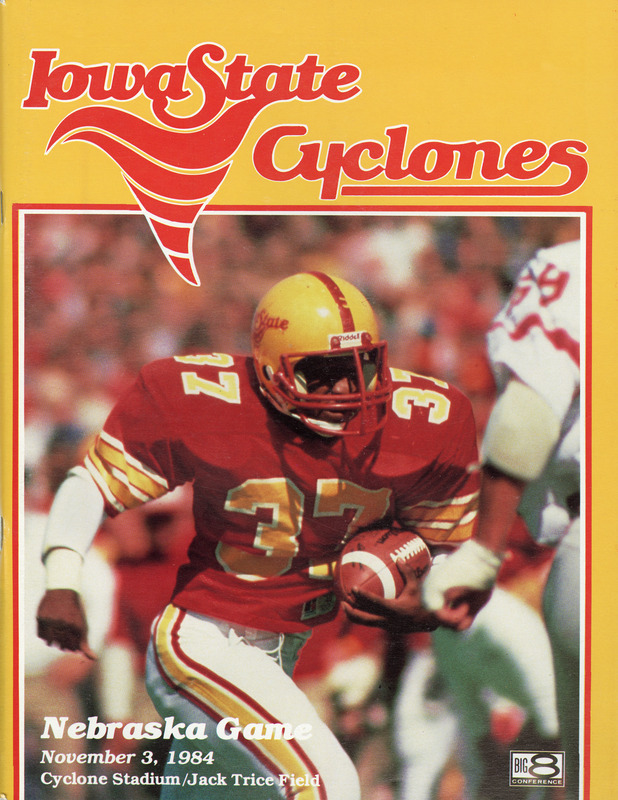

It was announced in September 1984 that the game on November 4 against Nebraska would see a ceremony to dedicate the naming of the new stadium and field. During the game’s halftime, a ceremony was held to formally dedicate the naming of the stadium and field.

In October 1984, the Government of the Student Body allocated $1,732 and formed a committee to organize a dedication ceremony for naming the field in honor of Jack Trice. On November 4, 1984, a dedication ceremony was held in the Great Hall of the Memorial Union to commemorate the naming of Jack Trice Field. The event started with a luncheon and was followed by comments from Donald Kaul, a journalist with the Cedar Rapids Gazette and longtime Trice Stadium supporter, and Chester Trice, Jr., Jack’s second cousin.

Transcript of Jack Trice Field Dedication Banquet hosted by the Jack Trice Dedication Committee, November 11, 1984. Committee on Lectures Records, RS 8/6/53, AV203430:

-

Dedication banquet. My name is Robert Broad, I’m the chairperson of the Jack Trice Dedication Committee. Over the past couple of weeks, the committee of five members has worked very hard to put on this dedication ceremony, but not nearly as hard as the students have for the last 11 years. Students have been struggling on this campus to get some tangible object to put in memorial of Jack Trice. Jack Trice is the first athlete and the only athlete ever to die in a struggle for his school. We’re dedicating the field today for the good things Jack stood for. Jack stood for loyalty. Loyalty to his family, to his school, to his race and to his country. These are the things that we often don’t see anymore in today’s life and we feel it is very important to give something that we can actually see in memorial of him. In lieu of that, we have invited some of Jack’s family, his first cousin Chester Trice Sr., and Chester Trice Jr., and right now Chester Trice Jr. would like to say a few words.

-

Good afternoon. Thank you for inviting us to share in this momentous occasion. It is a very moving moment for my father and I to be part of the tribute to Jack Trice. As my father has told me, Jack’s smile opened many hearts and doors, which caused many people to embrace him. He met all the expectations of his family, not only athletically, but academically. Jack’s dedication to excel as outstanding student and athlete is comparable to the accomplishments of Jesse Owens, Jackie Robinson, and many others who have paved the way for blacks of today. After his death, the family constantly told themselves to remember the times. They held out hope that later in their lives something positive would happen as a result of Jack’s death. And it has. As I stand before you, my heart is filled with joy because my father is here with me to witness a dream come true. It is with great pride and gratitude that I take this opportunity on behalf of myself and entire Trice family to express our sincere appreciation for the bestowing of such a covenant memoriam to the honor of Jack. The dedication, the perseverance displayed by the students, faculty, administration of Iowa State University, as well as the community as a whole to have the field named in Jack’s honor has proven to us that the spirit of fairness, justice, equality, and the right for every human to persevere and succeed is alive and well in this country of ours. Jack Trice will forever remain a legacy of the ideals of equality and respect among all men. From this day forward, let Jack Trice Field be remembered and a reminder that the battle for equality has been engaged, however, the war for equality is far from over. And I wanna thank you again for not letting Jack die in vain. Robert, on behalf of the Ford Motor Company, who wanted to share in this great opportunity of this moment, they would like to present you and the student body with a check for $1,000 to use as you see fit to the Trice Memorial Fund. Thanks so much.

-

Thank you very much, I’m sure you’ll relay our appreciation. This is a good time to show a couple of the things that Jack Trice Memorial Foundation and the Government of the Student Body have been working on as a living Memorial of Jack Trice. The first of these is a scholarship. Government of the Student Body last year set up a $10,000 trust fund to have an annual $600 scholarship for a student that sowed the same traits that Jack Trice did. The loyalty and the commitment to his race, to his school and to his family. And I would like to present these now to two recipients. Each will receive $300 and these are Theresa Martin and Alfred Motin. Another one of the things that we’re proud to be working on is the statute we are now compiling. We have an artist, his name is Chris Bennett from Fairfield, Iowa. He’s been working on a model for the last couple of weeks of what a statue would look like for the Jack Trice. We’re going to unveil it in a moment. Another thing that we’re also working on is a symbolic move of the plaque from State Gym that was put up in 1924 to honor Jack Trice and that was the first thing that they saw that brought back the whole movement of Jack Trice. And that’s on display over here. We’re going to be moving that down onto the football field, a symbolic move of it, starting out just as a plaque in the gym, but now it’s moved to the naming of a whole football field. Kevin, would you like to unveil the plaque for us? I think this deserves a round of applause. And now for our guest speaker, someone that needs very little introduction to this area of the country. His name’s Donlen Call, he’s now a reporter for the Cedar Rapids Gazette. He has been a big supporter of Jack Trice Movement for many years. He had in his column, he was the father of the Jack Trice curse, as many of you may have read about. And I would, on behalf of the committee, would very happily and proudly present Donlen Call.

-

Thank you, I feel a bit like an imposter up here today. I certainly was never a leader in the Jack Trice Movement. I came to it rather late, rather it came to me. In the form of that yellow and gold magazine containing clips relating his story, along with the suggestion that the new football facility in Ames be named after him. Well, I thought it was a terrific idea. It seemed to me that the story of a young black man who literally gave his life in the service of Iowa State football was the a stuff of which legends are made. When you consider what Notre Dame, not to mention Ronald Reagan, has done with George Gipp, who was nothing more than a pool hall bum, after all, it would seem that the wholesome figure of Jack Trice was a natural for a wholesome school like Iowa State. It made so much sense that I didn’t see how the movement could fail. I thought it would be easy to make the powers that be see the light. I was wrong. I had not accurately gauged the innate conservatism over those with responsibility for naming stadia. I love to use that word. It makes one feel so educated, stadia. Part of my misreading of the situation was due to the fact that I didn’t think it was that big a deal. I mean, I went to the University of Michigan where we called our football facility, The Stadium. I thought that was because we couldn’t think up a better name. I felt that once we in Iowa came up with a name that carried some meaningful symbolism, it would quickly carry the day. And I suppose another factor was that I really don’t like football. And the older I get, the less I like it. Forget the nature of the game, one can argue about that. To me, it is a minute and a half of thrills packed in just three solid hours. But I don’t like it because it too often perverts the educational purpose of a university. We find the public responding to schools on the basis of their success on the football field, rather than in the classroom. We have the spectacle of alumni becoming more upset about losing homecoming games then the loss of accreditation of one of their major departments. And we see colleges lying, cheating, and stealing to acquire football teams, while at the same time attempting to instruct students in ethics. Remember Robert Hutchins, the great educator when he took over as chancellor of the University of Chicago. The first thing he did was drop intercollegiate football and he said that was the absolute most important thing that he did to make Chicago a great university. Well, that’s an extreme view, but there’s a good deal of truth in it. Also, I don’t like football because of its brutality. It seems to me there’s something intrinsically wrong with a game where every few plays a young superbly conditioned is helped off the field or lies writhing on it in pain. So I took up the cause of Jack Trice casually, I must admit. I felt as long as you’re gonna play the damn game, you might as well play it in a facility named after a real football hero, rather than someone with big pockets. But I didn’t intend to make it my life’s work. As I said, it was harder than I anticipated. The naming of any public facility is a political act. One that must satisfy a variety of constituencies. I think some of the opposition to the Trice idea was frankly, racial. Some people simply didn’t want a stadium named a black man, however worthy. I suspect this constituted a minority of the opposition. Many more opposed it for practical reasons. If you’re going to enlist private money to build these facilities, you have to recognize the fact that the people who give you the money like their name up on them. We have the example of the arena at the University of Iowa named after that great Iowa athletic hero Roy Carver. And even so estimable an institution as Columbia University, this year put up a football stadium named after the guy who gave them the money for it. But to others the opposition was based on the sincere, to me misguided belief, that it was unfair to honor someone who had made so little a contribution to Iowa State football. Mr. Trice’s career, after all, had been cut short at it’s very beginning. They felt the gesture was sentimental and perhaps even trivial. Well, as the years wore on, I wrote more and more about Trice and the stadium. And I must admit in my characteristic way, I had fun with it. I invented the Trice curse, of which I think was one of my happier inventions, as a matter of fact. But in the process, I learned more about Jack Trice and the incident in the Minnesota game that cost him his life. Much of what I learned was contradictory. Every time I’d write a column, some old timer write me and he’d been at the game or perhaps knew Jack, and they always had a somewhat different version. Some said that the Minnesota team, indeed, had set out to deliberately injure Mr. Trice because he was black. Others said it was an accident. Some said it was partly Mr. Trice’s fault, because with misguided bravery, he tried to conceal the extent of his injuries. Given the times, my own view is that the Minnesota team had set out to deliberately injure him because he was black, but that’s neither here nor there. One thing all the letter writers agreed on, with remarkable unanimity, was that Trice was an enormously likable young man who brought to football and life, a naive enthusiasm and a warm, trusting spirit. As a writer once said of Joe Lewis, he was a credit to his race, the human. I began to think it was not merely right that Iowa State’s stadium should be named after him, it was important. For two reasons. The first one of which has nothing to do with his being black. Jack Trice was the embodiment of all that is good about college football, of which there is still a trace element left in the game. He stands for a time when football players were not paid gladiators, but students who played for the fun of it and out of a loyalty to their institution. They represented the university. I find that his letter to himself, written on the eve of his first and last game, both charming and quite moving. He asked for no special favors, but simply for a chance to compete. To be treated as an equal. As a man. And that indeed is what college athletics should be about. The opportunity to be judged on ability and effort, without regard to who you are or where you came from. In honoring him, Iowa State honors the very best of its athletic tradition. But we cannot ignore the fact that he was black. A black man preparing to make his way in a society that was implacably hostile to members of his race. And in honoring him as a black man, we honor all the black athletes who followed him to Iowa State and who made such an enormous contribution to this school. He stands as a symbol, a martyr if you will, to the black struggle in our society, one of many. And we must cherish their memories always. For these reasons, it seems to me, are enough to sweep aside the so-called practical objections to naming the stadium after him. Unfortunately, it didn’t happen. We didn’t win. They still named a stadium after a wind storm. But we did get the field named after him and that’s something. That’s a lot. Perhaps the future will see the name of Jack Trice Field fall into disuse. On the other hand, it might become the dominant label given to the field, you can’t tell. But we have done what we could to help keep alive the Jack Trice story. And that was worth doing because his story is worth remembering. You can’t always win the good fight, you know. You can only fight it. I think the Trice experience stands as a demonstration that the bad guys don’t always win. Sometimes they tie. I’m truly honored to be here today to share in this dedication ceremony. And I hope that the Iowa State Cyclones go out on that field today, Jack Trice Field, and tie Nebraska.

-

Thank you very much, Mr. Call. I can guarantee you one thing, Jack Trice won’t be forgotten. Students have worked 11 years for this. We’ve set up things that we know will last and students will not let it be forgotten. Jack Trice’s story is definitely something that should be remembered and we as students, and I know the students that will come, will not let this be forgotten. Many of you have heard of the letter that Jack Trice wrote that he pinned to his clothes the night before the game and that they found shortly after he died. I’d like to read that to you. It’s very moving and touching, and something that you can tell was written with very deep insight and thought. It starts out, October 5th, 1923. To whom it may concern. My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life. The honor of my race, family, and self is at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will. My whole body and soul are to be thrown recklessly about the field. Every time the ball is snapped, I’ll be trying to do more than my part. Fight low, with your eyes open, and towards the play. Watch out for cross bucks and reverse ends. Be on your toes every minute, Jack, if you expect to make good. Jack Trice. I’d like to thank you again for coming to this dedication ceremony. We will also be dedicating the football field during the halftime show and I hope to see some of you there. There will be buses waiting outside to transport us over to the football field, if you’d like. Thank you for coming.

Despite the University’s recognition of Trice by naming the football field in his honor in 1984, the student body still sought a “tangible object” to memorialize him, among other scholarships and awards. In 1985, GSB unanimously passed a resolution to allocate $22,000 toward erecting a Jack Trice statue. Artist Christopher Bennett of Fairfield, Iowa, was commissioned to craft this bronze piece, dedicated during the 1988 VEISHEA celebrations.

The statue was originally located on central campus outside of Beardshear Hall, moved in 1997 when the stadium was renamed, and ultimately replaced in central campus in 2019 to increase the presence of Trice’s legacy on campus. It has been said that the piece is larger than life to embody Trice’s extraordinary spirit.

The Trice family has remained a part of his story at Iowa State throughout the last century. In 1988, Herbert and Betty Armstrong, the daughter of Cora Mae Trice Greene (Trice’s widow) and her husband Homer Lee Greene, wrote to ISU President Gordon P. Eaton about their plans to visit Ames and see the newly erected statue of Jack Trice. They were shown around campus and took photos and videos to share with Cora Mae, who lived in California. In response, Cora Mae shared her gratitude for the students and other contributors who raised the money for the statue and her poignant recollections from the fateful events in early October of 1923.

847 Collingswood Drive,

Pomona, Calif. 91767.

August 3rd, 1988

Dr David Lendt,

Morrill Hall

Iowa State University

Ames, Iowa.

Dear Dr Lendt,

Thank you for Responding to the letter that my Daughter Betty Armstrong wrote you in regards to the “Jack Trice” Dedication.

Thank you for sending me the picture, Letter And the copies of the Dedication.

I wish to Thank the Students who raised the $22,000 to erect the Statue and all others Contributing. I Still have a picture and medals of His High School days, Also a necklace that I have treasured through the years.

Dr. Lendt “Jack’s[”] passing was a great shock to me! He was my First Love and I have many Beautiful memories of him and our short Life together.

The night that he was Leaving for Minnesota with his Coach, He came to tell me good bye, we kissed and hugged and he told me that he would come back to me as soon as he could.

The day of the game, I was at the game in Ames, I heard it announced that he had been injured. I stood and bowed my head and then I heard that he walked from the field. I felt some what relieved. Monday noon I was in the cafeteria. His Fraternity Bro “Mr Harold Tutt[”] came to get me and said that I was to go to the Campus Hospital, I did. When I saw him I said [“]Hello Darling” He looked at me, but never spoke.

I remember hearing the Campanile chime 3 o’clock. That was Oct 8th, 1923, and he was gone.

Sincerely Yours,

Cora Mae Trice Greene